I was recently invited to give a talk at the Toronto Reference Libary to staffers from around the city, with a fairly wide mandate of what topics I could cover. In an effort to discuss something that would be relevant to them, I thought I'd share my experience of going through the book-publishing process and where I thought the industry is headed. I was pretty nervous in talking about the subject because, while I do have some experience in the field, I certainly don't deal with books on an every-day basis like many in the audience did. I felt sort of like a Johnny-come-lately trying to tell them about stuff they knew intimately, and better than I did.

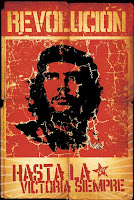

After giving the talk, I wondered if attendees thought I was crazy because I spoke of revolution and how everything about how books are made is going to change dramatically in the next few years. I'm fairly sure some people in the audience agreed with me, and I'm equally sure that some thought I was full of it.

My thoughts on the subject are probably familiar to anyone who reads this blog regularly. In a nutshell, the book industry hasn't seen as much impact from the digital revolution as the music and video businesses have as of yet, largely because reading electronic books hasn't really been that easy. E-books have been around for ages, but reading them on a computer screen has just been too painful to even consider.

With the advent of e-ink and the Amazon Kindle three years ago, the game changed. Indeed, the Kindle is revolutionizing the book business in the same way the iPhone did the phone business (ironically, they were released in the same year). Just as 2010 saw real competition finally arise for the iPhone in the form of Android, so too did the Kindle finally get good rivals with the likes of Kobo and others. But the devices are only half the story - they're also attached to new distribution systems. Amazon's is easily the best as the Kindle's "WhisperNet" feature lets you buy books via cellular connection wherever you may be, but there are also a handful of other good, big competitors with their own e-book stores, including Kobo, Sony, Apple and Google.

So, the revolution in how books are read and sold is already well underway, and e-book sales are skyrocketing as a result. The other revolution - the more interesting one that I talked about at the library - is in how books are written and created, and this part is only just now beginning. All of the online bookstores also offer authors - established and budding - the opportunity to self-publish their work. I've gone into the merits of this before, where self-publishing is potentially more lucrative for an author than having their book sold by a big-name publisher, so I won't rehash it here.

The Los Angeles Times, however, has an excellent story that covers off almost everything I talked about at the library, which makes me feel considerably less crazy. The reporter talked to a number of authors who said they plan to self-publish all of their work going forward because it's simply a better deal. The traditional publishing system holds very little appeal for them. "If an author has the choice of two distribution models, one that costs nothing and has no gatekeeper and the other has lots of gatekeepers and costs a lot of money, a lot of people will go with the free one," said Seth Godin, a best-selling author who has become something of a self-publishing guru.

I've talked about - to get a book published and ultimately sold, a writer has to go through a network of agents, editors, bookstore buyers and finally the media. Self-publishing largely removes all of those, which is why the Times story concludes with the thought that the only gatekeepers left will be the readers. I couldn't agree more.

Crime novelist Joe Conrath takes it further in the story: "If a traditional publisher offered me a quarter of a million dollars for a novel, I'd consider it. But anything less than that, I'm sure I can do better on my own."

That's exactly my plan for my second book. Not that I'm going to hold out for a cool quarter-million, but if I don't get offers that I like - or any offers at all, for that matter - I'll be perfectly happy to give it a go myself on Amazon and the others. There are many downsides to self-publishing - you have to get your own editors, designers and publicists - but ultimately it comes down to only one thing: brand versus brand. If an author has a strong enough name recognition, as many established writers do, there's actually very little they need a traditional publisher for. The rest can be done for a fraction of the price that publishers currently charge.

The challenge is for those of us who are not household names, and who are not yet trusted "brands" comparable to Random House or HarperCollins. But just as today's bands and film makers also have to be entrepreneurial to get their work noticed, so too will writers have to become more enterprising. There are plenty who will be happy to stick with the old system of gatekeepers, but there are also many of us - as evidenced by the Times story - that are just dying to do it for ourselves. Sooner or later, the traditional book industry is going to have to take notice of that fact and implement dramatic changes to how it does business with its most important customers: authors.

0 comments:

Post a Comment